George Lakey: Nonviolent Action & Climate Justice

This learning guide provides a brief overview of George Lakey’s work. It includes discussion questions to guide conversations and activities for students and learners of all ages.

Created by: Gabriel Smith, Jacob Gedetsis, Jonathan Nahar, Sarah Nahar, Brice Nordquist, Alex Scrivner, Isabel McCullough Valentín, and Dominic Wilkins

Environmental Storyteller Spotlight: Author and Activist George Lake

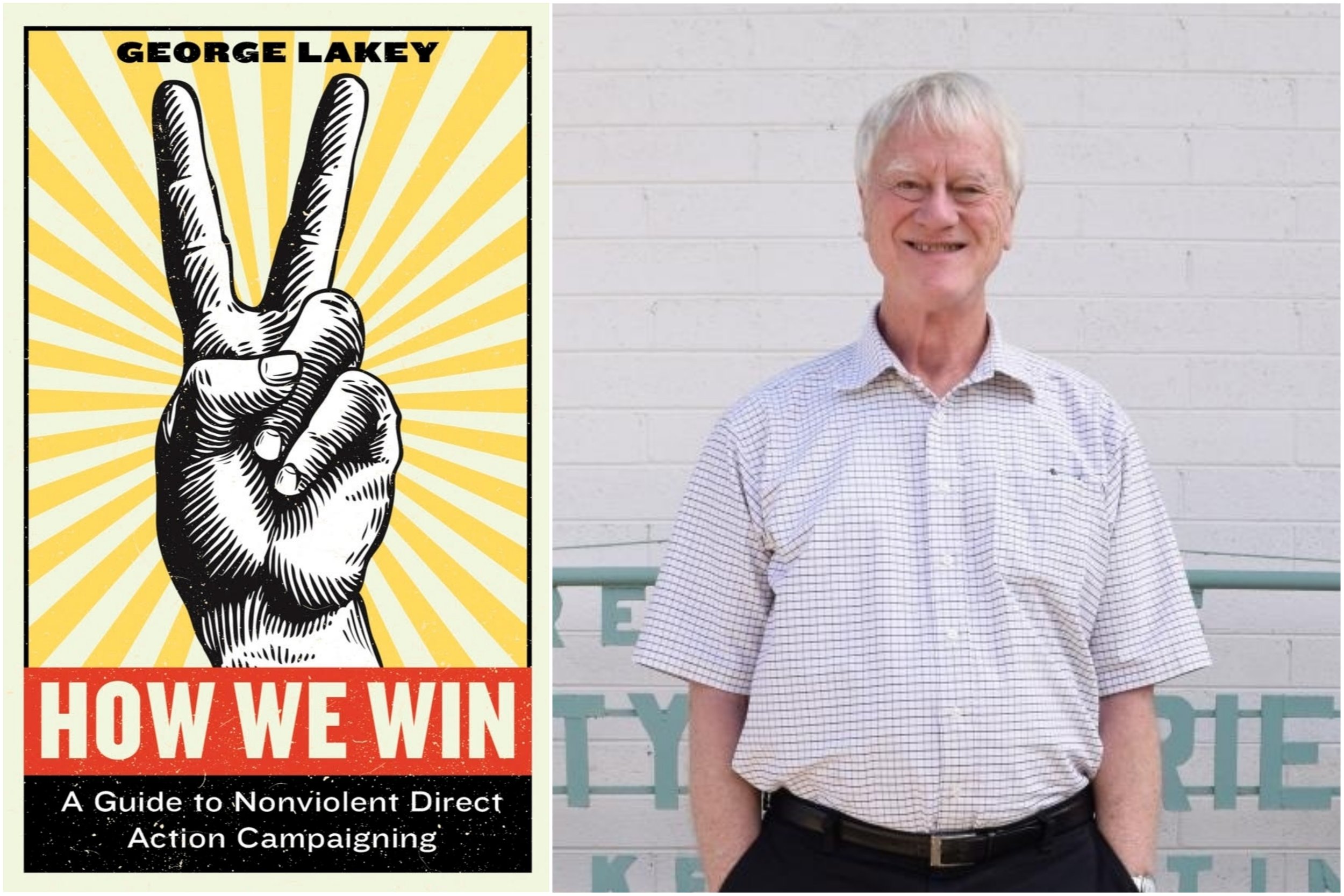

George Lakey was born into a white working-class family in a small town in rural Pennsylvania and has been active in direct action campaigns for seven decades. He recently retired from Swarthmore College, where he was a professor of Issues of Social Change. He is a Quaker, and came out as a gay man in 1974. Lakey was first arrested at a civil rights demonstration in March 1963, and his most recent arrest was in June 2021 during a climate justice march. He helped found numerous experiments in nonviolent living and social movement training such as the Movement for a New Society and Training for Change. These groups help everyday people develop tools and strategies to employ in order to bring about revolutionary change through nonviolent means. His books include Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians Got It Right and How We Can, Too and How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning and Dancing With History: A Life for Peace and Justice. He lives in Philadelphia. A motto that he lives by is “The revolution’s gotta be irresistible!”

Understanding the Environmental Story & Issue

Campaigns for Nonviolent Social Change

The last century has been a century of people power. From challenging war, racism, and sexism to resisting climate denial, grassroots movements made up of everyday people have created significant change. Figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mohandas Gandhi are well known in the history of nonviolent resistance, but the movements they were a part of were made up of thousands of people, acting together in a strategic, collective effort to achieve liberation. These movements achieved seemingly impossible victories over colonists, and opponents of equality. They did so through disrupting “business as usual” in their societies, in a nonviolent way that created cognitive dissonance for those doing the oppression.

Even though they faced violence, they were willing to do so because the causes of freedom, justice, and equality were worth intentionally sacrificing their time and energy for. A number of people in the Indian independence movement and the Civil Rights Movement were killed by those seeking to maintain the status quo. The memories of assassinated activists continue to inspire the movement. Some who were young during that era live to this day to share their stories with our generation.

George Lakey was one of those youth who was inspired. Born in 1937, He has lived a life infused with the spirit of activism, in community and solidarity with his neighbors. Recently, together with dozens of other grandparents and their grandchildren, George sat in a rocking chair and blocked a major intersection in Philadelphia for hours, outside of a bank that is funding fossil fuel extraction. This disruption of business as usual–making it much more difficult for the bank and the city to continue to make money for a number of hours, made it clear that we cannot go on exploiting the Earth if we hope to have a livable planet for future generations.

Today, George spends most of his time teaching communities about developing smart nonviolent direct action campaigns. “When a campaign inspires other campaigns, the sum of them becomes a movement” he says. Campaigns have as their target an entity, group, or person that can say “yes” to the demands of the grassroots campaigners seeking a change in the system. Using the grandparents’ example, a bank can divest a fossil fuel company sponsoring an oil pipeline from its investment portfolio, and instead invest that money in a renewable energy company. A series of campaign victories that target banks, businesses, local city ordinances that provide the pipeline company subsidies, etc., has turned the Stop the Money Pipeline into a national movement. This is how the civil rights movement worked, action inspiring action, creating cohesion of purpose inspired by a grand vision of what our society can be when we are all able to flourish.

It’s more than one protest

Many who respond to the call of grassroots organizers to engage in protests or direct action do so because they feel the need to do something, anything, in the face of indiscriminate violence, inequity, exploitation and impunity. Protests allow people to express their emotions and feel a part of a collective moment. That is important, but what to do when that moment passes? That energy is only captured and mobilized for durable change if the protest is part of a broader nonviolent action campaign. Training for the long run will enable “people power” to grow and change the direction of societal institutions. Going beyond the moment is critical because systemic change occurs over years and decades. Throughout the years of work, actions, planning meetings and potlucks, people who were once silenced find their voice, those who were marginalized by society play central roles in making change. Especially in the context of deep polarization, nonviolent action campaigns bring people together across lines of difference–they show what wonderful possibilities exist beyond the status quo as they make history.

There is a place for you in a nonviolent action campaign!

Activist movements are a way for individuals to gain insight into their own humanity, claiming a victory in their own life regardless of the outcome of the particular campaign. At their best, movements provide spaces for participants to experience the respect and dignity they deserve, preserving the spirit to continue fighting for justice and equity in society at large.

For sustainability and success, campaigns need different types of people taking up different roles and actions. There are those who are on the ‘frontline’. There are those that make lunch for those on the frontline. Everyone matters. Direct service, advocacy, behind the scenes organizing, and the consistent ‘critic’ who takes the meeting notes. Everyone is needed. Spiritual leaders can help keep everyone inspired, ‘care bears’ keep people safe during an action. What ties every roles’ efforts together is a shared vision, and a clear plan to achieve specific goals along the way. Campaign planning is key as it serves to focus efforts and build momentum from previous victories. Campaigns come from within a group’s own experience and respond to real challenges group members are facing. For example, the Montgomery bus boycott was 11 months of refusal to take public buses in which Black people had to sit in the back. Organizers planned for carpools, walking buddies, and held religious meetings every evening in order to keep people’s spirits up. This is covered in the must-see movie saga Eyes on the Prize.

“If we want to win, we’ll forget about the blaming and go directly to the renegotiating that needs to happen...”

George Lake on Nonviolent Action and Oral Histories

George says, “I can’t do anything without telling stories.” There is no better way to illustrate the lessons that come from significant events in history than to hear about them from someone who was there! This is oral history, hearing from people who have personal knowledge of past events. Through this method of storytelling, lived experience becomes primary source material, as people choose lessons from the past to seed possibilities for the future. Stories help to expand a listener’s imagination, and we remember a lesson best when we hear it in a story.

George chose Syracuse to be a part of his book tour for his memoir, Dancing with History. Reading a biography of someone’s life is one thing, and it’s another to hear them speak about difficult and joyful times, lessons learned, and key encouragement. He ties together his personal life journey and the life of the political movements in a way that becomes more than just one individual's reflection. His other book, How We Win is largely dialogue with young leaders that guide the reader to see in their own story, the opportunities for working together with others in collective action for the common good.

Some Terms to Know

Activist Campaign: A strategic and multifaceted attempt to remedy social, economic, and/or environmental injustices. Many people work together, using tactics such as sit-ins, pickets, or legislative advocacy in order to pressure power holders to change. They are the most successful when they push for specific, concrete changes in behavior and policy.

People Power: All governance and authority relies on the consent and participation of the governed. Leaders and members of activist campaigns have therefore fought to reduce the barriers to taking action. One barrier is that many people believe power sits at the top of institutions. Activists recognize that those being governed can wield great power when they act together, subverting or even undoing the systems of oppression, exploitation, and violence.

Nonviolent Direct Action: A tactic in a campaign working outside of established institutional pathways while refusing to use or even threaten injurious force. Some common methods include mass gatherings and blockades, noncooperation, boycotts, and occupations of public or privatized space for a sustained amount of time.

Civil Disobedience: This tactic of breaking unjust laws holds that no one should allow rules, laws, or coercion to overrule or degrade their informed conscience. Civil disobedience holds that all people share the duty to instead act for what they believe is just--even if that means breaking laws, refusing taxation, or otherwise rejecting authorities' orders.

Six Steps for Nonviolent Action: Derived from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s work, these six steps outline a path activist campaigns might follow. They are: 1) gathering information and 2) education which leads to 3) personally committing to change. From here, activist campaigns can 4) negotiate with those perpetuating injustice and, if unsuccessful, begin 5) direct action with the eventual aim of 6) reconciliation and justice.

Climate Justice: Many around the world and in the US experience the impact of the climate crisis every day. However, the effects of changing temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather patterns are not experienced equally. Those least responsible for climate change are bearing the brunt of its effects as a result of social inequality and systemic injustice. Climate justice insists that social and ecological justice are inseparable.

Discussion Questions

When you hear the word activist, what do you think of? When you hear the word nonviolent what do you think of? Do the words “nonviolent” and “activist” usually go together for you? Why or why not?

What are some major nonviolent direct action movements you know about today? How have people in your communities reacted to them?

Have you ever participated, or wanted to participate, in a nonviolent direct action? Why, or why not? If you have, how did you feel about the experience?

How does climate change make you feel? What does it make you want to do?

What do race, class, and queerness have to do with climate change?

What makes a law just or unjust? How should we respond to unjust laws?

Activities & Prompts

Below are writing prompts and activities for learners of all ages.

Intergenerational Interviews

Oral history is made up of stories that have been passed from generation to generation, mostly not written down, but remembered in detail by those who’ve heard the story. What is a story you remember hearing from your grandparents or another elder in your community? How did that story influence your life?

Try talking to someone who is 60 years older than you! Ask them about their life. See it as a kind of intergenerational interview.

Example questions:

What was a celebration they remember participating in?

What was an important event in time for this individual? How did it impact their life?

How do they define family? Is this different from earlier in their life?

What’s one of the biggest changes they have seen from their childhood compared to today?

Environmental Storytelling Intersections

Connecting the whole academic year’s storytelling series: Jason Corwin, Vievee Francis, SeQuoia Kemp, and George Lakey, we offer these suggested site visits and writing prompts:

Suggested Sites:

Destiny Mall

Syracuse Inner Harbor, site of approved $85 million aquarium project

Erie Canal walk

Onondaga Lake Park, on the north side

Elmwood Park, on the south side

The underpass of Interstate 81 between ESF’s campus and the elementary school

Your own favorite place

Think about the landscapes at this site. What stories do you know about this place? What “wilderness” is still visible? What is given space to grow? What is not? Who makes decisions about how these spaces get used? How do these spaces connect or divide us when it comes to mobilizing for systemic change?

Next, visit another site and ask what role it plays in movement building to rise against environmental injustices in our community, Central New York, and across the U.S.

Suggested Sites:

Sankofa Center on the south side

Community Folk Art Center

Syracuse Cultural Workers

Skä-noñh Great Law of Peace Center

The Jerry Rescue

Your own home or childhood neighborhood

Selected Additional Resources

These are a few of the organizations in the Syracuse area that have campaigns for positive social change that utilize the tactics of storytelling and nonviolent action!

Join one of their events or listservs to stay up to date.

And more!