Vievee Francis: Ecopoetry & Environmental Hauntings

This learning guide provides a brief overview of Vievee Francis’ work. It includes discussion questions to guide conversations and activities for students and learners of all ages.

Created by: Shumaila Bhatti, Lauren Cooper, Jacob Gedetsis, Khadija Mohamed, Sophie Stokoe, Alaina Triantafilledes, and Siela Zembsch

Environmental Storyteller Spotlight: Poet Vievee Francis

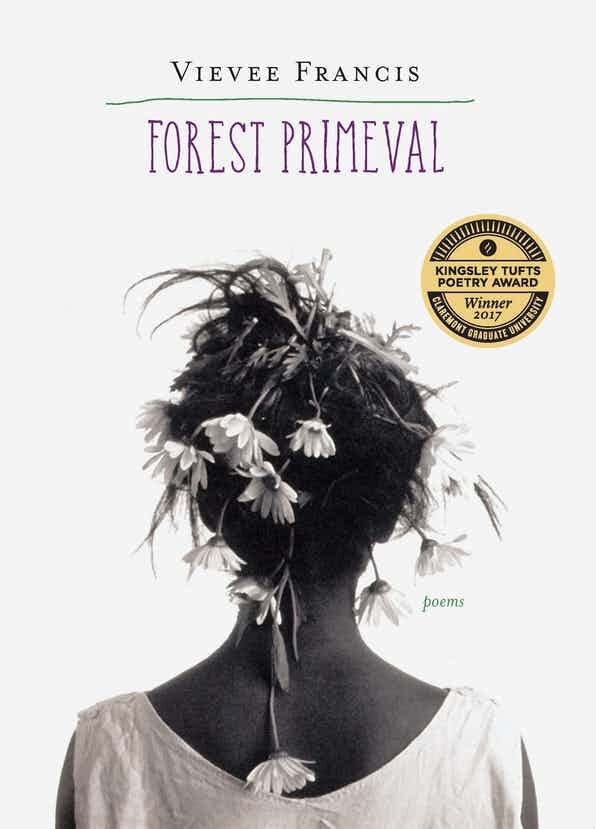

Poet Vievee Francis is the author of The Shared World, which is forthcoming from Northwestern University Press; Forest Primeval (TriQuarterly Books, 2015), winner of the 2017 Kingsley Tufts Award; Horse in the Dark (Northwestern University Press, 2012), winner of the Cave Canem Northwestern University Press Poetry Prize; and Blue-Tail Fly (Wayne State University Press, 2006). Her work has appeared in numerous print and online journals, textbooks, and anthologies, including Poetry, Best American Poetry, and Angles of Ascent: A Norton Anthology of Contemporary African American Poetry.

Understanding the Environmental Story & Issue

Environmental Hauntings: Undoing Ecological Mythmaking

Western ideas about why, how, and what type of nature matters and who gets to experience it come from Romanticism. Romanticism is a literary, aesthetic, and intellectual movement which peaked in the late 18th to the mid 19th century. One of the characteristics of the Romantic period was a renewed appreciation of nature, and of wilderness in particular, as having aesthetic and moral value. Romantic poets wrote enthusiastically about the individual in nature, and the importance of protecting, loving and living in nature. William Wordsworth is one of the key “nature poets” from this time period, and his poetry and prose is often considered responsible for the creation of national parks within North America and the UK.

Romantic aesthetic and ideological values continue to shape and influence our relationships with nature. The first national parks within the United States and Canada—Banff and Yellowstone with their massive snow-capped mountains and sparkling lakes— reflect Romantic ideas of the uninhabited sublime wilderness. However, prior to their establishment as national parks, Banff and Yellowstone were inhabited by indigenous populations. In order to become sufficiently “pristine” and “wild” for the educated wealthy elite who first patronized them, indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their land. The idea of the national parks as uninhabited natural spaces where nature is protected and conserved so that people can come visit and “get back in touch” with nature and wilderness is a profoundly man-made one—steeped in legacies of colonialism and violence. This model of historical environmentalism is rooted in the solitary individual in nature—an individual who is most often white, male, heterosexual, able-bodied, educated, and upper-class.

Modern environmentalists and environmental storytellers such as Vievee Francis urge us to consider alternate ways of understanding nature, not by forgetting the ways those other legacies and stories have shaped us and the ecosystems we inhabit, but by reckoning with these hauntings and responding effectively. Francis’s poetry collection, Forest Primeval, calls attention to how the stories we inherit about our shared environments shape our understanding of them. She draws on histories of slavery, blackness, intergenerational trauma, family history, personal history, literary history, environmental history, fairy tales, and blues music to write:

…my own nocturne. The lullabies I had forgotten.

How could I know what slept inside? What would rend my fantasies to cud and up

from this belly’s wet straw-strewn field—

these soundings. (“Another Anti-Pastoral”)

The conclusion of the opening poem of the collection, “Another Anti-Pastoral” is Francis’s ars poetica or poetic manifesto. In order to write her “own nocturne” she must return to the songs and stories she’s forgotten which are remade within the belly of her poetry and presented to the reader across the wet straw-strewn field of her poems.

Vievee Francis on Wildness and Wilderness in her Poetic Work

In Forest Primeval, Francis examines ideas of wildness and wilderness, not just within the natural world, but also within herself. This reflection takes place after she moves from Detroit to the mountains of Western North Carolina.

In an interview with The Los Angeles Review of Books, Francis states:

“The wilderness unraveled me — those boundaries of self and the performance of the self. And I had to confront myself in the wilderness — who I thought I was, and then there was the person I was becoming as I was there. The wilderness is so much larger than man. It took me off center, and I’m glad it did. It forced me to explore not just the natural world but the wilderness within me. Why was it unraveling me? That really was the starting point. I had to negotiate what the wilderness was doing to me, and there was no pretense that I was taming it. It was un-taming me!”

Francis’ “wilderness” overflows with the inherited hauntings of relationships, past and present. It binds and unwinds intergenerational trauma, blackness, environmental history, the language of landscape; it critiques and celebrates what is seen and unseen.

This confrontation of self, this unraveling, shines throughout her poetic work. Poetry, as a form, allows for this unraveling, allows for self-reflection in reaction to outside forces. Discussing the role of poetry in her life with Ms. Magazine, Francis noted:

“In my life poetry does not provide ‘healing’ but it does allow for expression and it markedly demonstrates that I cannot be silenced. I explore my interior and I relate it. Black women aren’t encouraged to do that. We are encouraged, even among progressives, to tow certain lines. My eccentricities don’t allow for that.”

We hope that Francis’ visit and work might provide a path to listen, better understand, and express that which cannot be silenced. Her work provides a chance to explore and respond to the wildness and wilderness within and around us.

Some Terms to Know

Defining Ecopoetry & Pastoral

Ecopoetry: “Ecopoetry” is a genre of poetry with a strong ecological emphasis. While the terms “ecopoetry” and “ecopoetics” grew out of the environmental movements of the 20th century, as the examples above demonstrate, humans have always been writing poetry about the ecosystems we’re part of. Ecopoetry most often carries with it an ethical imperative and sense of responsibility for the earth. It is an attempt to understand and critically engage with ecology, taking seriously the questions of ecological disaster, climate change, and the racist, sexist, and colonial legacies which have shaped not only our relationships with the environment, but also the environment itself.

Pastoral: The term “pastoral” is often used in three distinct—but related—ways. The first is historical and refers to a long literary tradition—beginning in poetry and then developed into other genres such as drama and fiction—which relies on certain common themes, styles, and techniques. This tradition has its roots in early Greek and Roman poems about rural country life, and about the lives of shepherds in particular. It is most often recognized as a form of return or retreat—a retreat from the urban into the rural, a return to the countryside as nostalgically remembered from childhood, or a retreat into the “good old days” where things are idealized as simpler, happier, and more wholesome.

These days, we often use the term “pastoral” to describe any contrast between the urban and rural, or the manmade and the natural, that tends to celebrate the rural and the natural, while criticizing—implicitly or explicitly—the urban and manmade. This leads into the third use of the word “pastoral” which is more critical, and often pejorative. “Pastoral” used in this sense—or “pastoralizing”, “pastoralized”—criticizes the pastoral vision as too simple and naïve. It is not an accurate depiction of life in the country, and refuses to acknowledge more complex ecological, economic, and social issues.

Discussion Questions

What do you consider the “environment”? What does it include and exclude?

Are there certain environments that evoke strong emotions? What are the conditions that cause those emotions to develop?

Francis explores both inner and outer landscapes. What does your inner landscape look like? Is your inner landscape affected by your physical landscape?

What does your writing tell you about your inner landscape?

Francis touches on altruism. What values connect you with your environment (based on how you define the environment)?

In what language(s) do you think, dream, and/or write? How do you think it may impact the way you experience storytelling?

Activities & Writing Prompts

Below are prompts and activities for learners of all ages.

The Pastoral and the Anti-Pastoral

Read and Discuss Francis’s two poems: Anti-Pastoral, Another Anti-Pastoral (p.3 in Forest Primeval)

What does it mean to write an “Anti-Pastoral” poem? Think about what Francis is rejecting and/or subverting, and what she is trying to keep or (re)create. Is writing an “anti-pastoral” a complete rejection of the pastoral tradition, or a challenge to it? Is she turning away from the pastoral tradition in “this is how Wordsworth would have it, / not red-eyed and trembling, but clearheaded, / the tempest assuaged. / Can you believe that?”? Or is she turning away from her own memories and prior poetry, as in “I want release from the pasture / of my youth, from its cows and cobs in the mouth. / Forgive me my tiresome nostalgia. / Forget it. / Let me forge a fissure between what was and is”?

In “Another Anti-Pastoral” what does it mean for Francis to “have fallen from my dream of progress: the clear-cut glass, the potted and balconied tree, the lemon-waxed wood over a marbled pillar, into my own nocturne. The lullabies I had forgotten”? She writes “I want to put down what the mountain has awakened” and then describes her poem as “My mouthful of grass”. How might a poem be a mouthful of grass? Is that anti-pastoral?

Creative Writing Prompt

Write your own pastoral or anti-pastoral poem (or both).

Follow Francis’ poems as a guide. When you look around you, do you see nature? What do you consider nature: trees and birds? or does the urban landscape count? Describe your environment in as much detail as you can. What images do you see when you look out a window of your house? What has nature “awakened” inside of you? Have “words failed you”? Or does this nature bore you? Does it feel distant? Do you feel like it belongs to you, and that you can write about it? How have your own memories, and the stories, poems, songs, and movies you’ve watched or grown up with shaped your understanding of your environment? What is “the pasture of your youth,” and how might you want to describe it to someone else in a poem?

Haunted Landscapes

Read and Discuss: “Skinned” (26), “Salt” (28), and “Paradise” (65)

These three poems explore how Francis’s relationship to the land around her has been shaped by the legacy of slavery. “Skinned” focuses on the speaker’s relationship with her grandmother who “had been skinned herself (so to speak) / in that her skin was so often examined and found wanting” with Francis declaring that “I’m as country as she didn’t want me to be”. “Salt” contrasts how her “Yankee” sister innocently experiences the unexpected pleasure of watermelon for dinner while the speaker and “a gentleman from Georgia” share a weighted moment of cultural connection: “I know what he knows. A whole history rides / the vehicle, the mule train, the wagon, the dust / track of my sister’s outburst. And we begin / to laugh hysterically. He for all the expected / reasons. And I, I laugh because somewhere / I want to cry.” “Paradise” opens with an epigraph from iconic blues musician Leadbelly and Francis’s command: “Don’t tell me, I was there. And the songs / are mine who slept there” and ends with her statement “…Unless your own clan molders / beneath those mounds, you don’t know, and / you can believe me or not”.

These three poems underscore how our relationships to the ecosystems we grow up in are shaped by the cultural legacies we inherit. Think about where you grew up, where your parents or extended family did. What do you know of the history of the area, of their histories within it? How have these experiences shaped yours?

Creative Writing Prompt

Pick a particular place, object, or story you’ve been told about your environment that has special significance to you. Why does it matter? How has it shaped the way you experience this environment? How might you write it in a poem? What would you want other people to understand, what knowledge might you lay claim to? What do you want to carry with you into the future? What is it that you, like the speaker in “Skinned”, “want to forget, but I have my mirrors”? How are these places “haunted” by the things you’ve experienced and the stories you’ve been told?

Mental Environments

Read and Discuss: “This is my name: a conversation with Vievee Francis” and “A Small Poem” (p. 91)

In her interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Vievee Francis talks about both natural and urban environments, and how those different landscapes make her feel:

“And I had to confront myself in the wilderness — who I thought I was, and then there was the person I was becoming as I was there. The wilderness is so much larger than man.”

“I wanted more and more to be inside the urban — and what I felt was the urbane. I have friends who live such lives; they live in Boston and New York, and they have potted trees. And I can’t say I don’t feel marvelous there! I do. [Laughs.] I feel this odd and false sense of safety. But it doesn’t mean it doesn’t feel good.”

“I think part of the reason why the wilderness undid me was because the city I built within me was fragile, and it could easily fall.”

On top of writing about the feelings these places evoke for her, Francis talks about how words and writing also inspire different emotions. She ties both writing and nature together as things that evoke these emotions as well as through the metaphors she used in “A Small Poem.” This can be seen through the line “the word grows from a note a hello a salutation / and plants itself like a spring dandelion seed that by / afternoon is full grown and blowing more seeds,..”

Creative Writing Prompt

Imagine your mind was a world full of different environments. What environments are your emotions stored in and what do those places look like? Are they natural landscapes? Or urban environments? What would it be like to visit these environments of the mind?

Additional Resources

In her interview with Ms. Magazine, Francis said that in the last decade she is “most drawn to work that transgresses, work that subverts the blanching norms and dares to upturn our staid, narrow, and still Victorian ideas of the feminine.” Below are works and poets she highlights in this interview:

Rocket Fantastic by Gabrielle Calvocoressi

In this form-bending work, Calvocoressi explores the landscape and language of gender and the body.

Magical Negro by Morgan Parker

Through personal narratives and poetic litanies, Morgan explores black womanhood, ancestral trauma, and black everydayness. These poems engage with interior and exterior politics—of both the body and society, of both the individual and the collective experience.

the blind pig by Aziza Barnes

These afro-surrealist poems examine the American South through essayistic prose. A writer and performer, Barnes interrogates and deconstructs assumptions around gender, race, and class.