Food Sovereignty: How Local Food Justice Organizers Advocate for Change

This learning guide provides a brief overview of food sovereignty in central New York . It includes discussion questions to guide conversations and activities for students and learners of all ages.

Writing Team: Olivia Fried, Gracie Gilcrist, Miryam Nacimento, Ella Roerden, and Mariah Willor.

Understanding the Environmental Story & Issue

Introduction to Food Sovereignty

Food sovereignty is the idea that people, not big companies, should decide what food they eat, how it’s grown, and who grows it. Think of a community garden where neighbors plant the foods they love and grew up with: cilantro for salsa, collard greens for Sunday dinners, or healing herbs their grandparents once used. They share tools, swap recipes, and work side by side, pulling weeds and watering plants. The food they grow is organic, fresh, and meaningful, not just something bought off a shelf. These everyday acts — planting seeds, cooking together, and sharing food — are powerful expressions of food sovereignty. At a time when grocery prices are high, fresh produce isn’t easy to find in every neighborhood, and an industrial food system fuels climate change and exploits animals and ecosystems for profit, these acts make a difference.

Food sovereignty was first introduced by the Mexican government and later brought to global attention by the international peasant movement La Vía Campesina in 1996. It’s more than just a concept; it’s a struggle for justice and a way of life. At its core, food sovereignty is about the right of people to grow the food that nourishes them, food that is healthy, meaningful to their culture, and grown in ways that respect the land, water, and those who tend it [1]. It puts decisions about food back into the hands of communities, allowing them to feed themselves with dignity, care, and a sense of connection.

In the U.S.—one of the wealthiest countries in the world—approximately 47 million people struggle with hunger [2]. This raises an important question: Why is there hunger in a country with so much wealth? The food sovereignty movement says the problem isn’t a lack of food. It’s the way food systems are organized. Today, a small number of powerful agribusinesses control much of the food we eat. They profit by selling seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers, and by promoting large-scale, export-focused farming. This system often pushes small farmers out, damages the environment, and makes it harder for communities to grow food in healthy, traditional ways. As a result, hunger persists, not because there isn’t enough food, but because of who controls it and how it’s distributed.

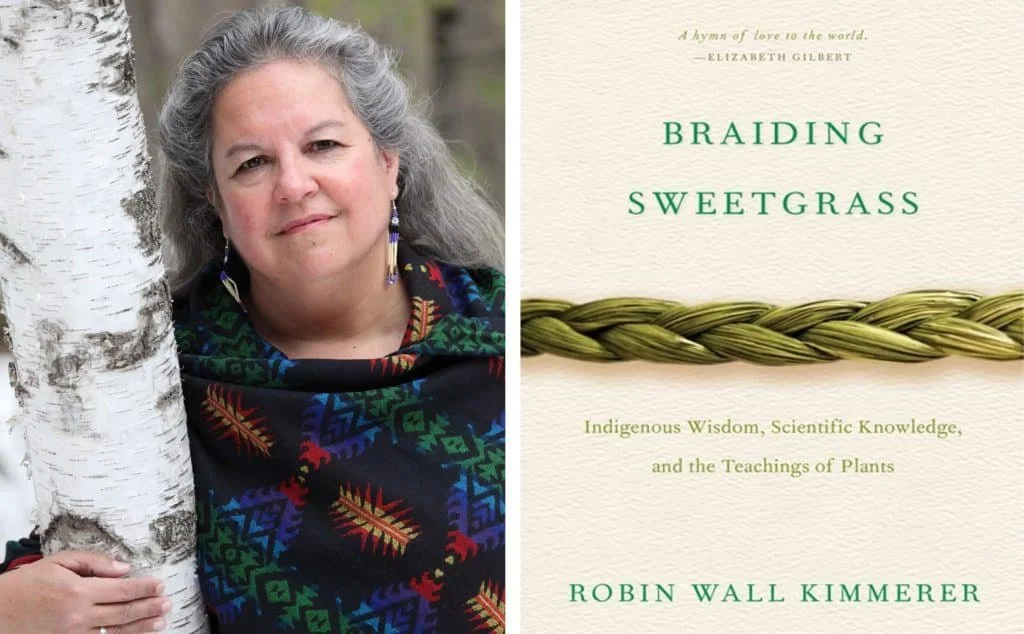

But, as Indigenous communities have long reminded us, food can be abundant when we care for the land with respect and reciprocity. Following the lead of the Onondaga people, this is one of the messages that the Syracuse-Onondaga Food Systems Alliance (SOFSA) is working to uplift in Syracuse, showing that a more just and nourishing food system is possible when communities reconnect with the land and with one another. Among many other initiatives, they host the Food Justice Gathering each year, a community event filled with conversation, celebration, and action. This year’s theme, Interwoven, is inspired by the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer, a prominent Native American scientist and writer. Her message helps us understand food sovereignty from an Indigenous perspective, one that values relationships, care, and balance with nature. It reminds us that food sovereignty begins with a renewed ethic of care, one that honors the land as a relative and sees justice as something we grow together.

This Learning Guide introduces the work of Angie Ferguson and Mariaelena Huambachano of the Onondaga Nation Farm and Braiding the Sacred, Monu Chhetri of Asha Laaya Farm and Deaf New Americans, and Mike Akins, who leads the Helping Hands Garden Program at MLK Elementary and the community garden at Hillbrook Juvenile Detention Center. As local food justice organizers and environmental storytellers, their work highlights how you can build more just food systems in your community and in our region.

References

[1] La Vía Campesina, “What Is Food Sovereignty?” La Vía Campesina, https://viacampesina.org/en/what-is-food-sovereignty/.

[2] Rabbitt, M. P., Reed Jones, M., Hales, L. J., & Burke, M. P. (2024). Household Food Security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR 337). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Video produced by Farm Aid.

Angela Ferguson, Onondaga Nation Farm

Mariaelena Huambachano, Braiding the Sacred

Located on reclaimed ancestral land just south of Syracuse, the Onondaga Nation Farm was founded in 2015 on a 164-acre plot. The Onondaga Nation is one of the six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, whose ancestral territory spans much of what is now called Central New York. What began as a modest effort (with five women tending to agriculture and five men dedicated to hunting and fishing) has since flourished. Today, the farm includes a vast network of volunteers, cultivation programs, a farmers’ market, and gatherings centered on traditional cooking.

Angela Ferguson, the farm’s supervisor, describes its mission as growing food in the traditional Haudenosaunee way, organically, as their ancestors once did, and giving it back to the community that nourishes it. For her, this is the essence of food sovereignty: “To show that we can feed thousands of people with what we produce here.” She notes that today the prevailing food system operates with a scarcity mindset, thinking “every man for himself” and accepting food scarcity as a given. “But that idea is foreign to us,” she says. Growing food, then, becomes more than just sustenance. It’s a silent form of protest, a powerful statement of autonomy. After the harvest, the food is shared in community gatherings that celebrate the return of Native foods to people’s diets, reviving Haudenosaunee nutrition, traditional cooking practices, and ancestral knowledge. These meals not only nourish the body but also mark a shift away from colonial foods that have fueled health crises like diabetes. As Angie puts it, “We have to think outside the box and imagine a new food system.”

The Onondaga Nation Farm serves as a vital gathering place for Braiding the Sacred, a grassroots network of Indigenous corn growers from across the Americas and the Pacific. This transnational initiative brings together Indigenous communities to reconnect with their sacred seeds through seed rematriation—the return of seeds to their original caretakers and territories, with the aim of preserving and revitalizing traditional varieties. Syracuse professor Mariaelena Huambachano, an Indigenous Quechua scholar from Peru, has played a central role in shaping this movement. Drawing on her experience in the Peruvian Andes, she helped facilitate the 2023 arrival of Sacred Corn seeds from Ayacucho, Peru, to the Onondaga Nation Farm. That seed-rematriation gathering convened growers from across the Americas and Oceania, cultivating a trans-Pacific community rooted in relationship, reciprocity, and solidarity. These gatherings are more than exchanges of agricultural knowledge—they are ceremonies of reconnection. Indigenous farmers bring seeds from their territories, share stories, reclaim foodways, and renew relationships with the land, with one another, and with the seeds themselves. As Huambachano emphasizes, seeds are not treated as commodities or genetic material, but as relatives: living beings with memory, spirit, and agency.

Corn, in particular, embodies this sacredness. Revered across Indigenous worlds, it is not merely sustenance but a divine gift—a source of life, a ceremonial presence, and a cultural anchor woven into creation stories and collective identity. This relational understanding is what distinguishes Indigenous Food Sovereignty. As Huambachano writes, “Indigenous Food Sovereignty transcends the legal aspect of the right to food (…) and underscores a relational, ethics-of-care approach to food imbued in an Indigenous cosmovision.”[1]

[1] Huambachano, M. (2024). Seeding a movement: Indigenous food sovereignty. University of Miami Law Review, 78(2), 390–409.

Monu Chhetri, Asha Laaya Farm and Deaf New Americans Advocacy

Down to the roots of its name, Asha Laaya Farm represents those it serves and is sustained by. Asha is the Nepali word for hope and Laaya is Burmese for farm. Asha Laaya is a 10-acre Deaf-led farm operated by the Syracuse non-profit, Deaf New Americans Advocacy, Inc. (DNA), which seeks to empower Deaf Immigrants, Refugees, and Asylum seekers.

Founder and CEO of Asha Laaya Farm, Monu Chhetri was born in Nepali descent in Bhutan and lived in a Nepal refugee camp for nineteen years. Monu, who is Deaf, works as an advocate, Deaf interpreter and educator, working to improve the lives of Deaf new Americans in Syracuse, New York, as well as support in other settlement communities in the United States.

“The important thing is that the farm is led by deaf people,so that in the future we could take this model and share it with others, with other deaf, new Americans all over America,” said Chhetri through an interpreter. “...Because so many deaf, new Americans are isolated and don't have this opportunity.”

Many of the farmers at Asha Laaya come from farming communities in Nepal and Bhutan, and are rich with traditional knowledge but in need of resources that organizations like DNA and Asha Laaya can provide. One of the struggles facing New Americans from communities around the world is the lack of access to culturally-appropriate foods, or foods traditionally eaten in their home cultures.

Often, food rights are explained through a lens of food security that merely considers access to food in general, and fails to consider the right of a people to healthy and culturally appropriate foods. By purchasing seeds of traditional vegetables and engaging in foraging practices, Asha Laaya fights to guarantee food sovereignty for all in central New York.

Video produced by Solon Quinn Studios.

“We use a lot of spices and herbs in our cooking, and to find these items, the best way is to grow our own,” said Jay Regmi, a Deaf farmer at Asha Laaya, through an interpreter in a virtual workshop.

In Nepal, Regmi could easily access traditional herbs and vegetables, like pumpkin fronds and the bathua plant, for free, but in the United States these ingredients are both hard-to-find and expensive. At Asha Laaya, DNA community members are offered free plots of land to farm their own vegetables and can take home what they grow. Farmers are also welcome to sell their crops at local farmer’s markets to support themselves and their families.

La Via Campesina defines food sovereignty, in part, by the ability to defend the interest and inclusion of the next generation. Asha Laaya pursues this goal not only through farming but also through a series of programs for the community. For CODAs, the children of Deaf New Americans, programs are offered to pass on generational knowledge such as recipes, cooking techniques, and the medicinal purposes of traditional herbs. Access to generational knowledge and teachings is fundamental to ensuring food sovereignty.

“Nothing about us without us,” said Chhetri through an interpreter. “That's my firm belief. Follow that. It's the most important thing. Always include Deaf people and Deaf new Americans.”

Mike Atkins, Community gardens at Dr. King Elementary and Hillbrook Juvenile Detention Center

In the heart of Syracuse, local leader Mike Atkins bolsters urban food sovereignty through his work with community gardens and youth. He helps oversee the Helping Hands Garden Program at Dr. King Elementary and the community garden at the Hillbrook Detention Center.

“It’s something that is worthwhile. If we introduce kids how to grow from a seed—that child will be more inclined to eat fresh vegetables,” said the former Syracuse city councilman in an interview with Syracuse.com article. “On a Sunday, if you have dinner with your family and your mother cooks the collard greens that you grew—that’s going to have an impact.”

Urban community gardens help address what activists and scholars call food apartheid. Food apartheid is what happens when certain areas of the community, usually ones with both high concentrations of Black, Latino, and immigrant populations, and high poverty levels, do not have consistent and convenient access to healthy food. This apartheid can come in several forms, from lack of grocery stores in walking distance to lack of food being healthy and simultaneously affordable.

A community garden at an urban elementary school provides students with much more than just a healthy snack. It helps empower them to make a difference for their families, it teaches them valuable skills to carry with them as they grow up, and it enables them to take their futures into their own hands, instead of those of the system.

Studies show that giving children practical education about food can make a huge difference culturally, financially, and nutritionally. Mike Atkins understands this, and his project is just one of many important urban community gardens both in Syracuse and across the country.

Setting up produce gardens within the community helps to provide healthy and costless options to bring home vegetables and fruits. These community garden projects are especially important in Syracuse, where they act to enable both food security and sovereignty for Syracuse residents.

In a city where most people do not have access to large-scale farms or land, urban food sovereignty can take the form of community gardens. Though they may not be very large, they can still be great places for various members of the community to join together in something that will benefit everyone.

One way Syracuse-Onondaga Food Systems Alliance (SOFSA) supports this coming together through community-led projects through its Food Justice Initiative. Last year, the organization funded projects like The Environmental Action Lab: Westside Ecofarm, which is working to transform a vacant lot on the West Side of Syracuse into a sustainable urban farm.

Anchored by the work of Syracuse Grows, Syracuse has a robust network of urban agriculture and community gardens. Syracuse Grows support more than a dozen community gardens with funding and resources in pursuit of food sovereignty.

“The garden teaches us to be independent. That is the key. From this little space, we can feed many people who can’t afford the expensive food at the grocery stores,” said Mable Wilson, a Syracuse food justice advocate that works with community gardens.”...By growing our food in the garden, we strengthen our community.”

Produced by Millrock Productions, Amy Toensing & Matt Moyer.

Some Terms to Know

Food Sovereignty: Food sovereignty is about the right of people to grow the food that nourishes them, food that is healthy, meaningful to their culture, and grown in ways that respect the land, water, and those who tend it. It puts decisions about food back into the hands of communities, allowing them to feed themselves with dignity, care, and a sense of connection (La Vía Campesina).

Seed Sovereignty and Seed Saving: The rise of commercial farming and seed corporations has created claims of seed “ownership” by large companies. Indigenous communities believe that farmers should have the right to save, use, exchange, and sell their own seeds. Seed saving is the process of saving seeds from one harvest for the next; Indigenous communities rely on certain crops for not only consumption, but for cultural and social purposes (First Nations Development Institute).

Food Justice: A social justice movement dedicated to ensuring the access to nutritional, affordable, and culturally appropriate food for all. (Boston University) An example of the food justice movement in Syracuse is Syracuse Grows, which helps broaden the access to food within the city by implementing, maintaining, and educating about community gardens and urban food production (Syracuse Grows).

Culturally-Appropriate Food: The idea that food must be understood within cultural identities, with regards to not only the food itself but also in how and who prepares and consumes it (Community Commons).

Food Deserts: Specific geographic areas (usually urban), where residents lack access either by affordability or distance to healthy nutritious foods. (Food Empowerment Project) ‘Food deserts’ is a great entryway term to begin thinking about the issues around food accessibility, however it is not the most inclusive and descriptive term. The term runs the risk of framing the issue of food inaccessibility as “natural” which is not true. This is why scholars have shifted to different terms and ideas like “Food Apartheid” instead.

Food Apartheid: Karen Washington, a food justice advocate, coined this term to reflect the linked social, racial, and economic factors that contribute to food accessibility, rather than solely the geographic location of residents (University of Michigan News). This accentuates the fact that the food justice movement is a complex social movement with connecting factors to other social movements, for example food apartheid highlights the need to acknowledge specific communities because of existing social structures that create this inequity. For example people of color tend to have less access to nutritious, healthy and affordable food, especially in highly segregated areas like Syracuse, this is linked to not only their geographic locations within the city but the structures that work against them to form this inequity in food access.

Discussion Questions

Where do you get your fruits and vegetables from (ie. grocery store, farmer’s market, CSA, home garden)? Is it ever difficult to get fresh produce? What has made it easier or harder for you?

If you could pick one fruit or vegetable to grow, what would you choose? Think carefully about the different ways it could be used and how it would help you.

What role can local institutions—such as universities and grassroots organizations—play in advancing food sovereignty?

Have you ever been to a community garden? If you have, think of the one thing you saw that interested you the most (a type of plant growing, a tool, anything you noticed!). If you haven’t, think of one thing you predict might be found at a community garden, and why you think it would be useful.

How can food sovereignty be practiced and imagined in urban contexts like Syracuse, where histories of racial segregation, economic decline, and corporate dominance shape access to food and land?

How do Haudenosaunee food practices—such as the cultivation of the Three Sisters —offer models for resisting extractive food systems?

Activities & Prompts

Below are writing prompts and activities for learners of all ages.

The Stories Plants Tell

Robin Wall Kimmerer describes the Three Sisters—corn, beans, and squash—as companions who grow together in mutual support. She reminds us that “plants tell their stories not by what they say, but by what they do.” The Three Sisters teach us about cooperation, patience, and reciprocity as ways of living well together.

(Optional) Read chapter “The Three Sisters” in Braiding Sweetgrass

Writing Prompt Activity:

Choose a plant (or food): It can be corn, beans, squash, or another plant that is meaningful to you. Perhaps one from your childhood, your culture, your community garden, or your kitchen today.

Give the plant a voice or a story: Imagine how this plant would tell its story—not through words, but through actions, relationships, or the way it grows and nourishes others.

Write a short piece (poem, prose, or letter): Describe the plant’s story.

Consider: What does the plant tell us about the culture it belongs to? How does it embody values of food sovereignty, like community, justice, or resilience?

Supporting food sovereignty with easy seed pod starters

Watch the following video to get started: Egg carton seed starters

Materials:

Cardboard egg cartons

Potting soil

Seed packets

A pen or small knife (for poking holes)

A spray bottle of water

Popsicle sticks (halved)

Scissors

Directions:

Start by cutting the lid off of the cardboard egg carton, then use a pen or small knife to poke drainage holes on the bottom of each egg compartment. For a classroom seed starter, the carton can be cut into individual pods for students to take home. Each compartment (pod) should be filled with a moist potting soil mix, ideally one with fine texture and added nutrients, which will support seed germination. The soil can be pre-moistened before adding to the pods, or sprayed with water after. Fill each pod ¾ of the way with the soil and press down to gently compact. Add 2-3 seeds per pod and gently push them beneath the soil using a popsicle stick. Leave the pods in a sunny place and keep them moist using a spray bottle. It can be helpful to label the pods by writing on the halved popsicle sticks, or simply by writing on the side of the carton. Germination times will vary depending on the species planted– the first sprouts should come about a week after planting. Once sprouted, these pods can be planted directly into pots, old plastic containers (yogurt containers, halved two-liter bottles/milk jugs, etc), or into the ground.

Food is a Universal Language

In the work of Angela Ferguson, Mike Atkins, and Monu Chhetri all approach growing, harvesting, and thinking about food in ways particular to their respective communities. Explore the Additional Resources below and consider the following questions.

Think and Write:

What foods do you eat everyday? Every month? Every year? Do you eat food in different seasons? For special occasions? What do your food habits reveal about your family, community and culture?

The Gift of Strawberries

In “The Gift of Strawberries” from Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer reflects on the difference between a gift and a commodity. Wild strawberries, freely given, taught her about abundance, generosity, and reciprocity. In contrast, strawberries at a commercial farm were commodities, bought and sold, stripped of relationship. Kimmerer reminds us that seeing the world as a gift fosters gratitude and responsibility, while viewing it only as a commodity creates disconnection.

(Optional) Read “The Gift of Strawberries” in Braiding Sweetgrass.

Think of something in your life that you have received as a gift. This might be a food, a plant, a recipe, a tradition, or even a moment.

Write and Discuss

Describe the gift: What is it? How did it come to you? How does it nourish or sustain you?

What responsibilities or feelings of reciprocity does this gift create? How do you give back, or how might you?

Can you recall a time when that same thing (or something similar) was treated as a commodity? How did that experience differ?

Write a short piece (poem, reflection, or story): Capture the difference between receiving something as a gift and encountering it as a commodity.

Selected Additional Resources

Additional Resources

Angela Ferguson, Onondaga Nation Farm

Video Resources:

Angela Ferguson of Onondaga Nation Farm on Food Sovereignty and Building a Sustainable Food System: Video (3 min) of Angela Ferguson discussing the logistics of the farm in an interview format- how it is funded, how it supports the community, the ideas and processes. Highlights the importance of recognizing the value of community and how this farm goes beyond feeding people, but giving people purpose and a place of belonging.

Indigenous Women’s Voices Series | Angela Ferguson: Video (10 min) about Angela Ferguson, focused primarily on Braiding the Sacred (https://braidingthesacred.org/about) and the work she does with the organization. Demonstrates Indigenous culture and sacred practices, includes video interviews of her discussing why she began her work, how, and a bit of history on her life and passions. (Contains videography of the plants and seeds themselves, the processes involved, and the materials needed for various steps of the process. Produced by Rematriation Magazine.)

Angie Ferguson: "Onondaga Nation & Food Sovereignty" - SOFSA | Syracuse-Onondaga Food Systems Alliance Video (43 min) containing a recorded talk given by Angela Furguson to the SOFSA membership in 2020, discussing her work with the Onondaga Nation Farm regarding food sovereignty, and her work with Braiding the Sacred focused on sacred seed recovering and distribution to support indigenous traditional crop abundance.

How Angela Ferguson works to bring pre-colonial foods back to Native American communities: Video (2 min) A clip from “Reclaiming Turtle Island”, a National Geographic project that Angela took part in. A brief overview of the Onondaga farm, their mission, their process. Discusses colonialism and its impact on traditional indigenous foods, the return of power through sovereignty, the importance of creating community and family.

2021 Ganondagan Husking Bee: A conversation with Angela Ferguson Video (1 hour) of a conversation interview of Angela Ferguson at the 2021 Annual Husking Bee, hosted by the Ganondagan State Historic Site and the Iroquois White Corn Project. Ferguson discusses the importance of food sovereignty as it relates to indigenous communities, practices, diet, and the building of community. (Casual discussion format video taken while she husked white corn. A lot of background noise, which makes her hard to understand at times- but contains a lot of interesting conversations and ideas.)

Haudenosaunee Traditional Cooking with Angela Ferguson (Onondaga Nation) Video (20 min) of traditional Haudenosaunee cooking styles, foods, and history. Includes interviews of Angela Ferguson and Chef Arlie Doxator, from the Oneida Nation, regarding their work with seed saving and the use and accessibility of traditional foods in maintaining community and preserving indigenous history.

Reading Resources:

Angela Ferguson of Onondaga Nation Farm on the Importance of Saving Seeds - Brooklyn Botanic Garden (full article on the Brooklyn Botanic Garden website)

Article/interview about the farm, her process, her history with food sovereignty, discussion of Carl Barns and his impact (can be connected to resources about Barnes), and even discusses the importance of and how to open rooms for conversations about Indigenous knowledge and foodways.

Thousands of historical seeds preserved by the Onondaga Nation Farm - ICT: Article about work that the Onondaga Nation Farm is doing actively with, how it started (back to Carl Barns), and their mission. Includes photos of the seeds and drying corn, and quotes from Angela Ferguson.

Monu Chhetri, Asha Laaya Farm and Deaf New Americans

Video and Podcast Resources:

Our New Neighbors, Episode 13 – Deaf New Americans Advocacy, Monu Chhetri |WCNY (25 min)

A podcast episode about Monu’s life in Nepal and her current work in Syracuse as the founder of Deaf New Americans Advocacy, Inc, in an interview format assisted by a deaf interpreter. (Transcript is also available through the link.)

A video without dialogue that gives an overview of the kinds of work and activities available through the Asha Laaya farm, focusing on their achievements in 2024.

Episode 79: Unlocking Big Lessons from a Deaf New American - Food Dignity® (1 hour)

A podcast episode containing an interview with Monu Chhetri, where she discusses her story of life as a New American, the barriers she faced accessing healthcare and food, and her work with local farms in creating opportunities for the deaf community and other New Americans. (Provides a detailed discussion takeaways section that briefs the main topics of the discussion.)

Deaf New Americans Advocacy / Asha Laaya

A video of Monu Chhetri discussing the Asha Laaya farm and their work with Deaf New Americans, along with their mission to create community, support heritage, culture, and tradition, combat food insecurity and financial independence, and support traditional food sovereignty.

Reading Resources:

Monu Chhetri endured her dad’s death, war, refugee camp, and an arranged marriage to break ground in CNY - syracuse.com (Warning: contains graphic depictions of her life, including the civil war in Bhutan, time at a refugee camp, and an arranged marriage resulting in teen pregnancy). This article introduces Monu Chhetri, the Founder and CEO of Deaf New Americans, and provides an overview of her life history and mission in an interview format. She also talks about the importance of leadership and gives advice on leading effectively with understanding and compassion.

Deaf New Americans find community at Asha Laaya 'Farm of Hope' An article discussing the mission, history, and community of Asha Laaya Farm, which works with Deaf New American volunteers to build community and support the accessibility of locally grown produce in Central New York.

Mike Atkins, Community Gardens at Dr. King Elementary and Hillbrook Juvenile Detention Center

Video resources:

https://www.localsyr.com/video/a-community-garden-at-one-local-school/6732044 A video from a newschannel that contains interviews at Dr. King Elementary and shows off their community supported urban garden. Also discusses the importance of access to fresh produce and the issues associated with the lack of access. (Has ads)

Reading resources:

Article about the opportunities awarded to students at Dr. King to grow their own food using hydroponics and composting systems, which includes interviews with students and staff about the program.

Student Sow Seeds of Change with Community Garden

An article about the garden at Dr. King Elementary School and its benefits to the students, faculty, and surrounding community, and includes photos.

Other selected resources:

About Us – Onondaga Nation - A reading about the Onondaga Nation and their general history as a nation. Additional resources about specific cultural practices, government structure, and other relevant information can also be found on the website.

How Indigenous food sovereignty can tackle food insecurity | The University of British Columbia : A video from the University of British Columbia defining food sovereignty from an Indigenous perspective, with mention of cultural resurgence, the necessity of access to medicinal and edible plants, and the impacts of climate change on these resources. Additionally, briefly discusses working with Indigenous communities as a non-indigenous person and how to work with that (regarding the way this land is treated and considered in western vs non-western perspectives) with a focus on land-based learning. (3.5 min)

The Story of Glass Gem Corn: Beauty, History, and Hope – Native-Seeds-Search

Article about Carl Barnes, an indigenous farmer and seed collector, and his seed distribution with a focus on Glass Gem corn. Highlights the mass reduction of available seeds and the importance of maintaining seeds and their accessibility.

SOFSA | Syracuse-Onondaga Food Systems Alliance

Website containing information about SOFSA and their mission, resources available, and how to get involved with their programs.

Deaf New American Advocacy Inc

Website with links to information about DNA, their services and mission, and local events.

Community gardens can change cities. Cultivate more than food. - YouTube

A video about the importance of urban community gardens and their benefits to health, combating food insecurity, and building community.

A reading about the history of Food Justice that contains definitions of language used when talking about food insecurity and the importance of food sovereignty, with a specific focus on marginalized groups.

Frontiers | Urban Agriculture Education and Youth Civic Engagement in the U.S.: A Scoping Review

A scientific article about the impacts of urban agriculture education on future civic engagement, entering the scope of self-reliance, the support of community, and the desire and ability to be an active and positive member of that community. Additionally highlights the importance of community gardens in urban areas and their benefit to students, focusing on community building, and the surrounding community, focusing on the reduction of food insecurity and access to fresh and nutritious produce.